Niky Ceria: “Bouldering is a humanistic matter”

.%20Photo%20Rudy%20Ceria.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

It was already last year, while I was looking for information about the Grampians, that I came across a now-hibernating blog filled with climbing photographic artefacts, travel reports from bouldering areas all over the world, and musings on ethics. But what intrigued me the most were the author's views and narrative. The figure of Niccolò Ceria piqued my curiosity even more as I came across his more recent material, which confirmed what had drawn me to him: the intimate and human perspective on bouldering. In this conversation, the transalpine climber explains how his motivations go far beyond the process of sending a problem, how imagination plays an important role in his work, and how factors external to climbing can compromise its true essence.

Niky is an example of someone who, when climbing, uses both his body and his soul.

«Clique aqui para a versão em português do Q&A»

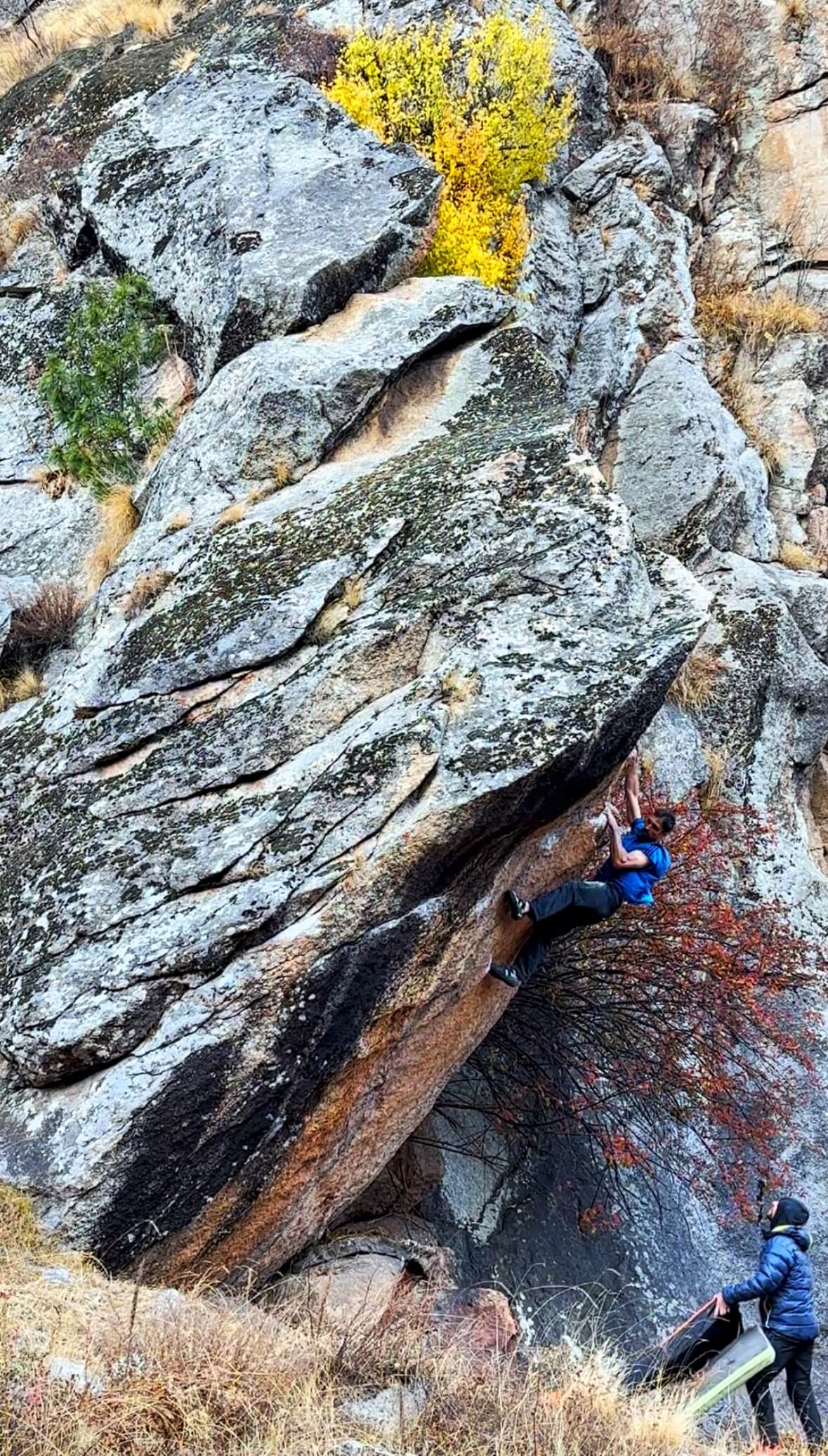

(Niky Ceria on Traumshiff - Zillertal (AUT))

(Niky Ceria on Traumshiff - Zillertal (AUT))

Born in a country surrounded by mountains, you’ve been mostly drawn to bouldering compared to other disciplines. What shaped your preference?

Essentialism and intricacy at the same time. While I have rarely felt attracted by the mountains, bouldering gives me the possibility to have the entire path where the experience unfolds within a single eye-frame: I can see it all in its deep details and visualize a sharp and remarkable connection between each minimal feature. Therefore I like the shapes that the boulders make.

I enjoy the variety and the possibilities that bouldering offers, especially when these ones are linked with your inner creativeness.

Another preference regards the movements and the style of the climb: often short, essential, conditions-dependent, tricky and focus-demanding.

I like the holds that boulders shape, while it’s difficult to find this quality on other climbing terrains especially consistently enough to cover a whole sequence of movements.

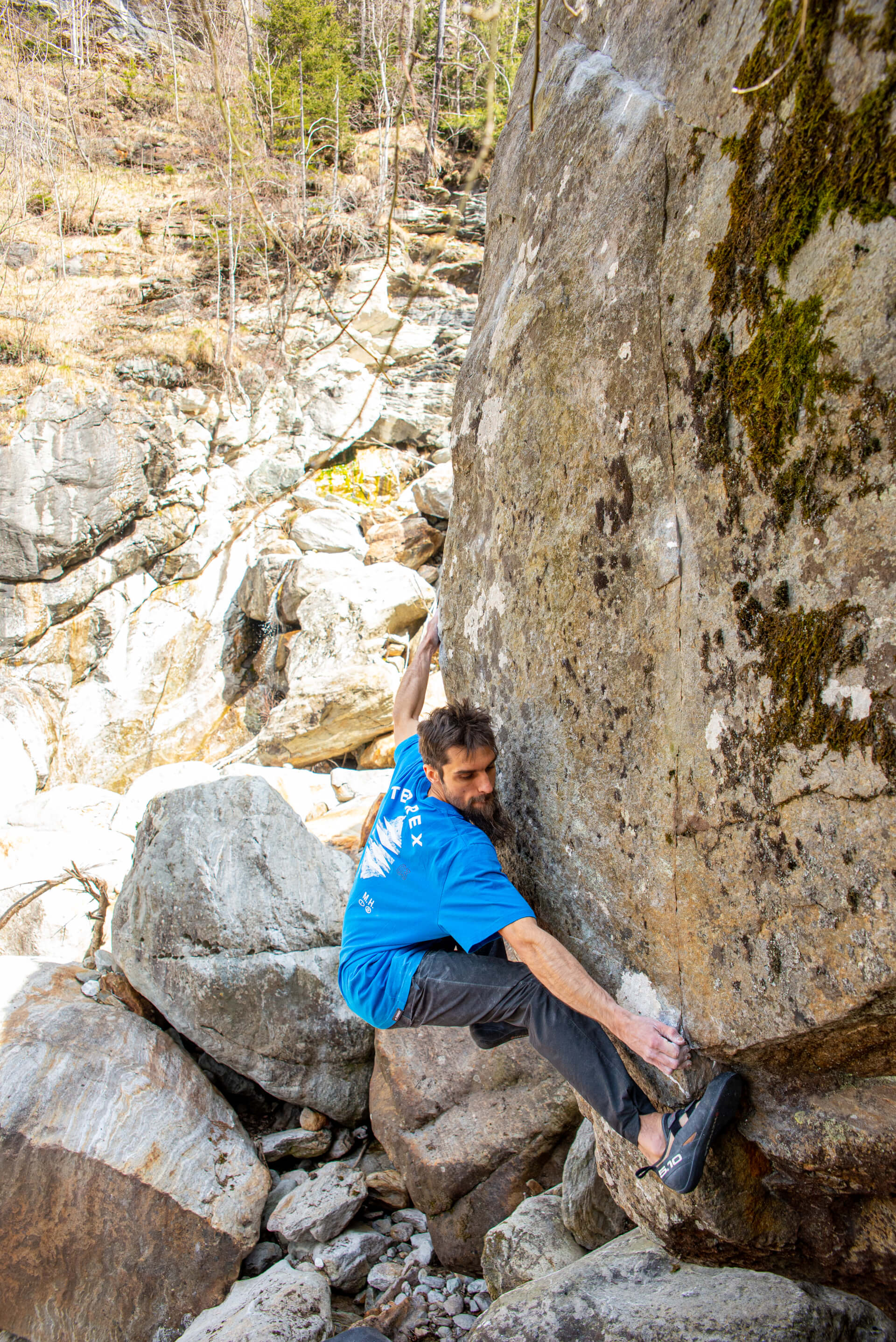

(Niky Ceria - Ticino (CHE))

(Niky Ceria - Ticino (CHE))

Something that defines you as a climber is how deeply you immerse yourself in climbing history and in the characters who developed the lines you plan to climb. Could you tell us how important the humanization of bouldering is for you? Has a lack of information about lines or areas ever diminished your interest in them?

I have to tell you that, sometimes, it’s true the opposite: the lack of the information and the fact that the community tends to ignore certain lines for silly biases - see ‘The Rail’, ‘Emotional Landscapes’, ‘Stepping Stone’… - makes me more curious and more motivated to unbury what’s hidden. Even if this is never the main reason that moves me towards a specific problem, I like to wonder why something gets so ignored by the media.

Bouldering is a humanistic matter. Every boulder, every climber and every sequence is a different story which can’t be matched with each other. So the human part is what makes all the difference and the one that tells you the most about a character, a piece of rock, an area, a process...

Sport, training and being able to perform become to me useful means for this richer level of bouldering: they have the same value as having a lot of pads to protect a fall or logistics skills to plan a difficult journey; they are all part of the same toolbox for living a way of climbing which is dense of human stories, different points of views, art and variety in the way we express ourselves.

Understanding this point was crucial to me. When my drive shifted towards this type of research and it became the ultimate meaning of my climbing, I found that my bouldering was fully in line with what I perceived inside.

(Niky Ceria on La Merveille - Fontainebleau (FRA))

(Niky Ceria on La Merveille - Fontainebleau (FRA))

Is imagination an essential part of your work? Does it ever conflict with your expectations?

Expectation can be a big enemy nowadays.

The closer it gets to this sort of rational-logic-perfection, the easier it will be to get disappointed. So it’s up to us how to use certain types of media. Today’s biases, often built up with many digital contents (reels, so not real), erase what’s beneath a video: moods, efforts, preparation, visualization, creativity, approaches, reality, commitment, emotions and many other aspects. Coping with this sort of AR is sometimes hard work especially because the true reality will always appear different, slower and more human-time-based.

The big trap of this system is the risk that part or most of your drive might spring from exogenous factors and so from something which comes from the outside. My personal experience is that the more inner and endogenous points we find to build our path, the better we will live climbing because it will be finally enriched by a deeper meaning. So this leads me to learn more and more how to use the contents out there for pure information. It’s not always easy to detach what can be useful from what can turn out to be a toxic expectation; avoiding this last bit can pay off well. I often avoid thinking about having always the beta through the videos (especially for the first sessions) because it can infect my process towards a solution that might work for me. This is why I often end up finding different betas on classics or using new expedients to face some of the moves. It’s very interesting and it makes you improve a lot in the long term.

(Niky on the Second Ascent of Bernd Zangerl's testpiece 'Die Versorgungslinie' - Himalayas (IND). Photo: Bernd Zangerl)

(Niky on the Second Ascent of Bernd Zangerl's testpiece 'Die Versorgungslinie' - Himalayas (IND). Photo: Bernd Zangerl)

Another point that’s worth to mentioning is that basically 90% percent of the popular things I repeat are previewed by a reality check: a walk to the boulder with no pads/shoes just to check how it is and get a real idea of it, approaching without any biases or trying to delete them in case there are some. Removing external biases is definitely much more useful than having tons of info and coping with them. This leaves much more gap for the imagination that can finally play its role in the experience.

Imagination is key if someone wants to find their own paths. For me, when scoping new areas or new lines, imagination becomes not only important but the true protagonist of the experience. It’s like the most genuine ingredient and it joins you from the very beginning to the end of the process. Expectation is inversely proportional to imagination. The less you have of the first, the more you’ll find of the second. Expectations often provide you with quick and ephemeral joys which are more similar to illusions in the end, even if they can be sweet in the short term. In imagination the time slows down, the meanings are more endogenous and the satisfaction of something that has been fully imagined can last forever.

(Niky Ceria on the First Ascent of Indice Obbligazionario - Aosta Valley (ITA))

(Niky Ceria on the First Ascent of Indice Obbligazionario - Aosta Valley (ITA))

You do a lot of research before your climbing trips. Have you ever been surprised by what you found? Could you name a few places that exceeded your expectations?

Luckily, I learned to remember all the trips I made for what they were in real life and my memories run to what I have truly lived. So there is no real match with what I was expecting. Not only because I am now trying to start from a white canvas, but also because when something is done and it’s in the past, I tend to contemplate it for what it was. I don’t see a lot of significance in trying to dig into what I had previewed.

I am also reserving some doubts about the fact that everything needs to be enjoyable nowadays. To give you an example, I took a trip to Japan last November. It was hard for me and not really pleasant. But I want to get back in order to re-live the discomfort that shocked me and navigate its awkwardness again. Once I was back home I felt it was a tough but fulfilling experience because I could look into myself with different lenses.

(Niky Ceria on the First Ascent of Ghost of the Navigator - Aosta Valley (ITA))

(Niky Ceria on the First Ascent of Ghost of the Navigator - Aosta Valley (ITA))

You’ve developed some areas yourself, but beyond that, you prioritize individual lines, especially aesthetic ones. Could you describe the features you look for when searching for new boulder problems?

I think I have mentioned in some videos that, when analyzing a line, I try to consider 6 to 7 different macro points such as quality of the rock, line, aspect, holds, movements and environment. Each of them has several minor points as subcategories. But I doubt this can be something exhaustive and clear about my research, especially about the meaning of my climbing days. In the end, a piece of rock needs to strike a chord in me and I need to be touched by it. Perhaps it needs to make me feel certain emotions and perceive particular sensations. Of course, having more of these features in one single scenario can be gratifying. But in the end, I find the list of points to be a bit too rational and methodical for the reality which is, as I said, very connected to my inner part, my emotions and my soul. I don’t think we can really measure it or serve it on a menu; I am also quite concerned about people’s desperate need for measuring personal things. Bouldering is one of these in my opinion.

(Niky Ceria on the First Ascent of 'Biotronic' - Castle Hill (NZ))

(Niky Ceria on the First Ascent of 'Biotronic' - Castle Hill (NZ))

In a Sam Lawson’s video, you mentioned that only Biotronic (NZ) could match the feeling of climbing Bombadil (UK) to you. One was a first ascent and the other a repetition. Does your heart pound differently when you’re approaching your own lines compared to when you’re repeating someone else’s?

The scenarios and the contexts that “FA” label hides are quite remarkable.

I was the first climber to top out on ‘Biotronic’ but it was shown to me as a notorious project: I didn’t explore or find it, I didn’t need to clean it, visualize it or imagine the line and some other parts of the whole FA process weren’t really included. I think I also had some bits of beta explained by a friend of mine. The FAs that I participate in with a process from A to Z (where A is going out for a hike and see if you can find pieces of rock and Z is topping out something that wouldn’t have been new if not for your vision/research/work) usually go through a completely different path than Biotronic, so I’d not say that I have approached it as one of my own lines.

Biotronic was a special one because of a handful of unique factors: it was the first project that got shown to me in New Zealand and it was already mentioned to me before planning the trip. I did the final arête ground up. It took me 4 days to understand the balancing move and it came out to be a very satisfying one. That day the weather went through all 4 seasons more than once, including snow and so nobody really expected that the slab would have been doable again so this added an extra surprising and sweet factor. I was younger and the energy of that trip was special. I was one of the first Euro climbers exploring the island… so many things summed up to create one of the most special moments, if not the most special moment, of my career.

Also, would I be able to do something like that again? Sometimes I wonder about this...

Probably the fact that, thanks to my ascent, one of the longest and proudest projects of the island was finally completed added a bit of importance to the feat and therefore it added one more thing that Bombadil’s experiences couldn’t have. But what I wanted to mention in the video is that Bombadil was hands down the most special experience I have ever had in repeating a boulder.

I didn’t really take into account if my heart pounds for things differently, but probably those processes from A to Z that I mentioned before could be quite deep. Not sure though if I feel like comparing two such bigly different ways of approaching bouldering.

(Niky Ceria on the Second Ascent of Bombadil - Christiambury (UK). Photo: Dan Varian)

(Niky Ceria on the Second Ascent of Bombadil - Christiambury (UK). Photo: Dan Varian)

Over the years, you’ve traveled extensively around the globe, yet you seem especially drawn to the UK. What keeps you returning?

I have several returns to the UK but even more trips back to Basilicata, Australia, Red Rocks, Fontainebleau, Northern Europe.. I think the UK gets asked more because it is the last area where I have returned. This makes me assume that people often remember only the last things that happened, regardless of what has been done earlier or if something more striking happened in the past. It offers me an assist to remind people to always extend their consideration time when talking about climbing. At least 15-20 years.

The UK has special things as well as the places I have mentioned above. I particularly like Northumberland: sandstone, moors, silence, good avenues, positive vibes at the gym, Dan Varian’s visions, vicinity with Kielder Forest and so e-bike adventures.. and a handful of king lines.

(Niky Ceria on the First Ascent of Sua Maestà - Aosta Valley (ITA))

(Niky Ceria on the First Ascent of Sua Maestà - Aosta Valley (ITA))

Is there any boulder problem or climbing area you haven’t had the chance to try yet but are excited about?

Yes, there are still some remarkable ones both considering the areas and the boulders. But I am not going to spoil them here. Or not all of them. 😊

So I can tell you that it has been ages since I want to go to Arkansas and Latin America.

On a more regional scenario, since a couple of friends spoke well about Sintra, Portugal could be a good Euro destination one day.. in case any of your readers would be keen to show me around 😊

Youtube | Instagram | Facebook | Blogspot

Additional credits:

Cover image - Niky Ceria on the First Ascent of Aeropressing - Sardinia (ITA). Photo: Rudy Ceria